Apush Chapter 28 Review Questions Identification Iron Curtain

Petty Rock schools closed rather than allow integration. This 1958 photograph shows an African American loftier school daughter watching school lessons on boob tube. Library of Congress (LC-U9- 1525F-28).

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click hither to amend this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- II. The Rise of the Suburbs

- 3. Race and Education

- Iv. Civil Rights in an Flush Society

- Five. Gender and Civilisation in the Affluent Society

- VI. Politics and Credo in the Flush Lodge

- 7. Decision

- VIII. Primary Sources

- IX. Reference Cloth

I. Introduction

In 1958, Harvard economist and public intellectual John Kenneth Galbraith published The Affluent Society. Galbraith's celebrated volume examined America'south new post–World State of war Two consumer economic system and political culture. While noting the unparalleled riches of American economic growth, information technology criticized the underlying structures of an economy dedicated only to increasing product and the consumption of appurtenances. Galbraith argued that the U.S. economic system, based on an almost hedonistic consumption of luxury products, would inevitably lead to economical inequality as private-sector interests enriched themselves at the expense of the American public. Galbraith warned that an economy where "wants are increasingly created by the process past which they are satisfied" was unsound, unsustainable, and, ultimately, immoral. "The Affluent Order," he said, was anything only.i

While economists and scholars argue the merits of Galbraith's warnings and predictions, his assay was and so insightful that the championship of his book has come to serve equally a prepare label for postwar American gild. In the two decades later the stop of World State of war II, the American economy witnessed massive and sustained growth that reshaped American culture through the abundance of consumer goods. Standards of living—across all income levels—climbed to unparalleled heights and economic inequality plummeted.two

And yet, equally Galbraith noted, the Affluent Society had fundamental flaws. The new consumer economy that lifted millions of Americans into its burgeoning middle class likewise reproduced existing inequalities. Women struggled to claim equal rights equally total participants in American order. The poor struggled to win access to good schools, good healthcare, and good jobs. The same suburbs that gave middle-grade Americans new infinite left cities withering in spirals of poverty and crime and caused irreversible ecological disruptions. The Jim Crow South tenaciously defended segregation, and Blackness Americans and other minorities suffered bigotry all across the land.

The contradictions of the Affluent Society defined the decade: unrivaled prosperity alongside persistent poverty, life-irresolute technological innovation alongside social and environmental devastation, expanded opportunity alongside entrenched bigotry, and new liberating lifestyles alongside a stifling conformity.

Two. The Rise of the Suburbs

The seeds of a suburban nation were planted in New Bargain government programs. At the top of the Slap-up Depression, in 1932, some 250,000 households lost their belongings to foreclosure. A yr afterwards, half of all U.S. mortgages were in default. The foreclosure charge per unit stood at more one chiliad per day. In response, FDR'south New Deal created the Dwelling house Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), which began purchasing and refinancing existing mortgages at chance of default. The HOLC introduced the amortized mortgage, assuasive borrowers to pay back interest and principal regularly over fifteen years instead of the then standard five-year mortgage that carried large balloon payments at the end of the contract. The HOLC eventually owned well-nigh one of every five mortgages in America. Though homeowners paid more for their homes nether this new system, home ownership was opened to the multitudes who could now gain residential stability, lower monthly mortgage payments, and accrue wealth as belongings values rose over fourth dimension.iii

Additionally, the Federal Housing Assistants (FHA), another New Deal organization, increased access to home ownership by insuring mortgages and protecting lenders from fiscal loss in the upshot of a default. Lenders, nonetheless, had to agree to offering low rates and terms of upwardly to twenty or thirty years. Even more consumers could beget homes. Though merely slightly more than a tertiary of homes had an FHA-backed mortgage by 1964, FHA loans had a ripple effect, with private lenders granting more than and more abode loans even to non-FHA-backed borrowers. Government programs and subsidies like the HOLC and the FHA fueled the growth of home ownership and the ascent of the suburbs.

Government spending during World War 2 pushed the United States out of the Depression and into an economic blast that would be sustained after the war by continued government spending. Regime expenditures provided loans to veterans, subsidized corporate enquiry and development, and built the interstate highway system. In the decades after World State of war 2, business concern boomed, unionization peaked, wages rose, and sustained growth buoyed a new consumer economy. The Servicemen's Readjustment Human activity (popularly known equally the G.I. Bill), passed in 1944, offered low-interest home loans, a stipend to attend college, loans to kickoff a business, and unemployment benefits.

The rapid growth of home ownership and the rise of suburban communities helped drive the postwar economic boom. Builders created sprawling neighborhoods of single-family unit homes on the outskirts of American cities. William Levitt built the first Levittown, the prototypical suburban community, in 1946 in Long Island, New York. Purchasing big acreage, subdividing lots, and contracting crews to build endless homes at economies of scale, Levitt offered affordable suburban housing to veterans and their families. Levitt became the prophet of the new suburbs, and his model of large-scale suburban development was duplicated by developers across the country. The country's suburban share of the population rose from 19.5 pct in 1940 to xxx.seven per centum by 1960. Dwelling ownership rates rose from 44 percent in 1940 to almost 62 per centum in 1960. Betwixt 1940 and 1950, suburban communities with more than ten thousand people grew 22.one percent, and planned communities grew at an astonishing rate of 126.1 percent.4 As historian Lizabeth Cohen notes, these new suburbs "mushroomed in territorial size and the populations they harbored."v Betwixt 1950 and 1970, America'due south suburban population nearly doubled to seventy-four million. Fourscore-3 percent of all population growth occurred in suburban places.6

The postwar construction smash fed into countless industries. As manufacturers converted from war materials back to consumer goods, and as the suburbs adult, appliance and automobile sales rose dramatically. Flush with rising wages and wartime savings, homeowners as well used newly created installment plans to buy new consumer goods at once instead of saving for years to brand major purchases. Credit cards, first issued in 1950, further increased access to credit. No longer stymied by the Depression or wartime restrictions, consumers bought countless washers, dryers, refrigerators, freezers, and, all of a sudden, televisions. The pct of Americans that endemic at to the lowest degree i television increased from 12 percent in 1950 to more than 87 percentage in 1960. This new suburban economy as well led to increased need for automobiles. The percentage of American families owning cars increased from 54 percent in 1948 to 74 per centum in 1959. Motor fuel consumption rose from some twenty-two million gallons in 1945 to around fifty-nine million gallons in 1958.vii

On the surface, the postwar economical boom turned America into a state of affluence. For advantaged buyers, loans had never been easier to obtain, consumer appurtenances had never been more accessible, single-family homes had never been and then cheap, and well-paying jobs had never been more than abundant. "If you had a college diploma, a dark suit, and annihilation between the ears," a businessman later recalled, "it was like an escalator; y'all just stood at that place and yous moved upwards."8 But the escalator did not serve everyone. Beneath aggregate numbers, racial disparity, sexual discrimination, and economic inequality persevered, undermining many of the assumptions of an Affluent Society.

In 1939, real estate appraisers arrived in sunny Pasadena, California. Armed with elaborate questionnaires to evaluate the city'due south building weather, the appraisers were well versed in the policies of the HOLC. In ane neighborhood, near structures were rated in "fair" repair, and appraisers noted a lack of "structure hazards or flood threats." All the same, they concluded that the surface area "is detrimentally affected by 10 owner occupant Negro families." While "the Negroes are said to exist of the better course," the appraisers concluded, "it seems inevitable that ownership and property values will drift to lower levels."ix

Wealth created by the booming economy filtered through social structures with built-in privileges and prejudices. Simply when many middle- and working-class white American families began their journeying of upwards mobility by moving to the suburbs with the help of government programs such as the FHA and the G.I. Bill, many African Americans and other racial minorities institute themselves systematically shut out.

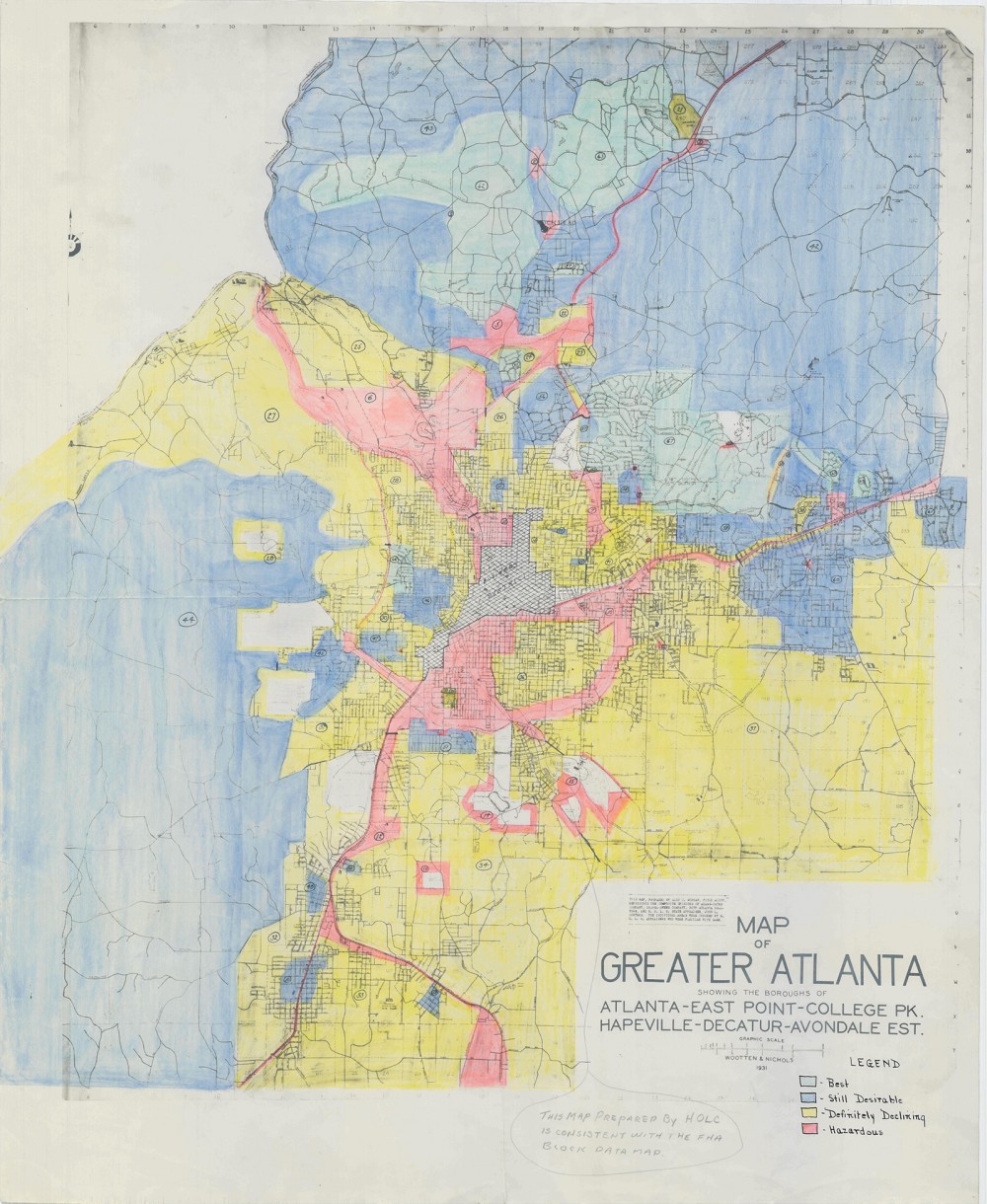

A look at the human relationship between federal organizations such equally the HOLC, the FHA, and private banks, lenders, and real estate agents tells the story of standardized policies that produced a segregated housing marketplace. At the core of HOLC appraisement techniques, which reflected the existing practices of private existent estate agents, was the pernicious insistence that mixed-race and minority-dominated neighborhoods were credit risks. In partnership with local lenders and real estate agents, the HOLC created Residential Security Maps to identify high- and low-risk-lending areas. People familiar with the local existent estate marketplace filled out uniform surveys on each neighborhood. Relying on this data, the HOLC assigned every neighborhood a letter grade from A to D and a corresponding colour lawmaking. The least secure, highest-risk neighborhoods for loans received a D grade and the color carmine. Banks limited loans in such "redlined" areas.x

Black communities in cities such as Detroit, Chicago, Brooklyn, and Atlanta (mapped here) experienced redlining, the process past which banks and other organizations demarcated minority neighborhoods on a map with a red line. Doing so made visible the areas they believed were unfit for their services, directly denying Black residents loans, merely likewise, indirectly, housing, groceries, and other necessities of modern life. National Archives.

Phrases similar subversive racial elements and racial hazards pervade the redlined-area description files of surveyors and HOLC officials. Los Angeles'south Echo Park neighborhood, for instance, had concentrations of Japanese and African Americans and a "sprinkling of Russians and Mexicans." The HOLC security map and survey noted that the neighborhood'southward "adverse racial influences which are noticeably increasing inevitably presage lower values, rentals and a rapid subtract in residential desirability."11

While the HOLC was a fairly short-lived New Bargain bureau, the influence of its security maps lived on in the FHA and Veterans Assistants (VA), the latter of which dispensed G.I. Bill–backed mortgages. Both of these government organizations, which reinforced the standards followed by private lenders, refused to dorsum bank mortgages in "redlined" neighborhoods. On the one hand, FHA- and VA-backed loans were an enormous boon to those who qualified for them. Millions of Americans received mortgages that they otherwise would not have qualified for. Just FHA-backed mortgages were not available to all. Racial minorities could not get loans for property improvements in their own neighborhoods and were denied mortgages to purchase property in other areas for fright that their presence would extend the crimson line into a new community. Levittown, the poster kid of the new suburban America, only allowed whites to purchase homes. Thus, FHA policies and individual developers increased home ownership and stability for white Americans while simultaneously creating and enforcing racial segregation.

The exclusionary structures of the postwar economy prompted protest from African Americans and other minorities who were excluded. Fair housing, equal employment, consumer admission, and educational opportunity, for example, all emerged as priorities of a brewing ceremonious rights motility. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with African American plaintiffs and, in Shelley v. Kraemer, declared racially restrictive neighborhood housing covenants—belongings deed restrictions barring sales to racial minorities—legally unenforceable. Discrimination and segregation connected, even so, and activists would keep to button for fair housing practices.

During the 1950s and early 1960s many Americans retreated to the suburbs to enjoy the new consumer economic system and search for some normalcy and security subsequently the instability of depression and war. Only many could non. It was both the limits and opportunities of housing, then, that shaped the contours of postwar American society. Moreover, the postwar suburban boom not only exacerbated racial and form inequalities, it precipitated a major environmental crunch.

The introduction of mass production techniques in housing wrought ecological destruction. Developers sought cheaper state ever farther fashion from urban cores, wrecking havoc on especially sensitive lands such equally wetlands, hills, and floodplains. "A territory roughly the size of Rhode Island," historian Adam Rome wrote, "was bulldozed for urban development" every yr.12 Innovative construction strategies, authorities incentives, high consumer need, and low free energy prices all pushed builders away from more sustainable, energy-conserving building projects. Typical postwar tract-houses were difficult to cool in the summertime and oestrus in the winter. Many were equipped with malfunctioning septic tanks that polluted local groundwater. Such destructiveness did non get unnoticed. By the time Rachel Carson publishedSilent Spring,a forceful denunciation of the excessive use of pesticides such as DDT in agricultural and domestic settings, in 1962, many Americans were already primed to receive her message. Stories of kitchen faucets spouting detergent foams and children playing in effluents brought the indicate home: condolement and convenience did not accept to come at such price. And nonetheless nearly of the Americans who joined the early environmentalist crusades of the 1950s and 1960s rarely questioned the foundations of the suburban platonic. Americans increasingly relied upon automobiles and arcadian the single-family domicile, blunting any major push button to shift prevailing patterns of land and energy use.13

Iii. Race and Teaching

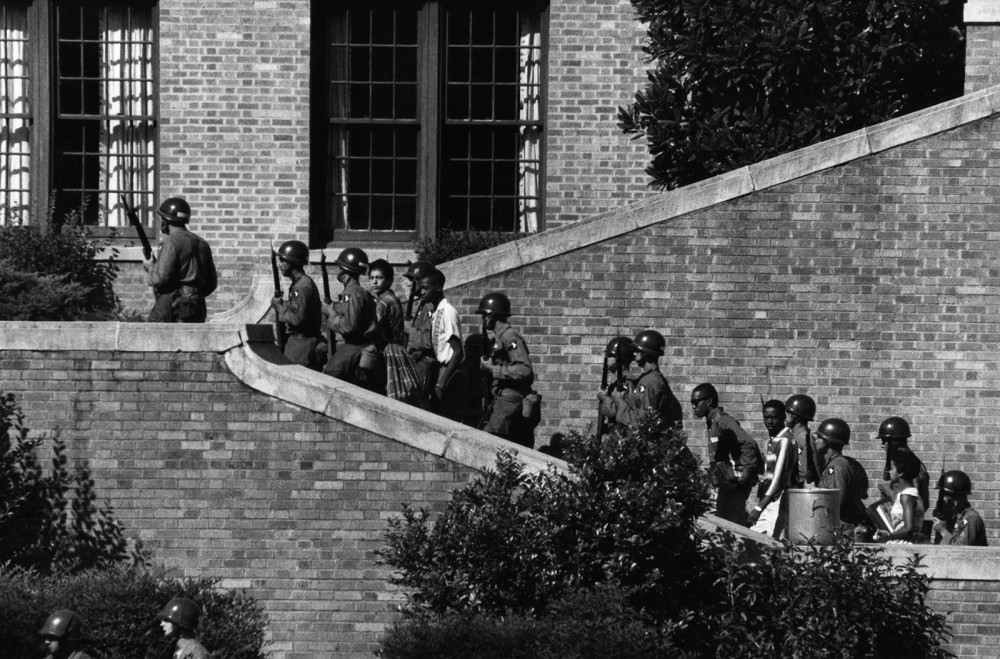

School desegregation was a tense experience for all involved, but none more then than the African American students who integrated white schools. The Little Stone Nine were the start to do so in Arkansas. Their escorts, the 101st Airborne Sectionalization of the U.S. Army, protected students who took that commencement step in 1957. Wikimedia.

Older battles over racial exclusion also confronted postwar American gild. 1 long-simmering struggle targeted segregated schooling. In 1896, the Supreme Court declared the principle of "separate but equal" constitutional. Segregated schooling, however, was rarely "equal": in do, Black Americans, particularly in the S, received fewer funds, attended inadequate facilities, and studied with substandard materials. African Americans' battle against educational inequality stretched across one-half a century earlier the Supreme Court again took upwards the claim of "separate but equal."

On May 17, 1954, after two years of argument, re-argument, and deliberation, Master Justice Earl Warren appear the Supreme Courtroom'south determination on segregated schooling in Brownish v. Lath of Educational activity (1954). The court found by a unanimous 9–0 vote that racial segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The courtroom's decision declared, "Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." "Separate merely equal" was fabricated unconstitutional.14

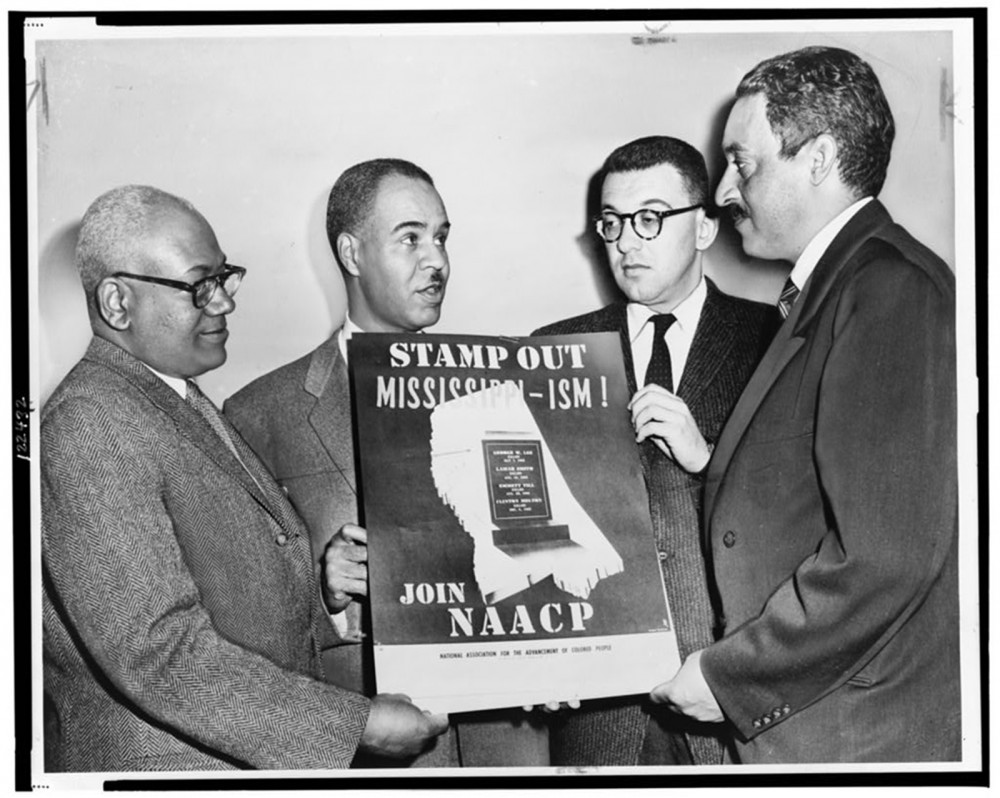

Decades of African American–led litigation, local agitation against racial inequality, and liberal Supreme Court justices made Brown possible. In the early 1930s, the NAACP began a concerted attempt to erode the legal underpinnings of segregation in the American South. Legal, or de jure, segregation subjected racial minorities to discriminatory laws and policies. Law and custom in the South hardened antiblack restrictions. Only through a series of carefully called and contested court cases concerning didactics, disfranchisement, and jury selection, NAACP lawyers such equally Charles Hamilton Houston, Robert L. Clark, and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall undermined Jim Crow'due south constitutional underpinnings. These attorneys initially sought to demonstrate that states systematically failed to provide African American students "equal" resources and facilities, and thus failed to live up to Plessy. Past the belatedly 1940s activists began to more forcefully challenge the assumptions that "separate" was constitutional at all.

The NAACP was a primal organization in the fight to end legalized racial discrimination. In this 1956 photo, NAACP leaders, including Thurgood Marshall, who would become the start African American Supreme Court Justice, concord a poster decrying racial bias in Mississippi in 1956. Library of Congress.

Though remembered as just one lawsuit, Dark-brown v. Board of Education consolidated five separate cases that had originated in the southeastern Us: Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina), Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (Virginia), Beulah v. Belton (Delaware), Bolling v. Sharpe (Washington, D.C.), and Brown v. Board of Education (Kansas). Working with local activists already involved in desegregation fights, the NAACP purposely chose cases with a diverse fix of local backgrounds to prove that segregation was not merely an outcome in the Deep South, and that a sweeping judgment on the fundamental constitutionality of Plessy was needed.

Briggs 5. Elliott, the first instance accustomed past the NAACP, illustrated the plight of segregated Black schools. Briggs originated in rural Clarendon County, Southward Carolina, where taxpayers in 1950 spent $179 to educate each white educatee and $43 for each Black student. The district's twelve white schools were cumulatively worth $673,850; the value of its lx-1 Blackness schools (mostly dilapidated, overcrowded shacks) was $194,575.15 While Briggs underscored the S'south failure to follow Plessy, the Brown adjust focused less on textile disparities between Black and white schools (which were significantly less than in places like Clarendon Canton) and more on the social and spiritual degradation that accompanied legal segregation. This case cut to the basic question of whether "separate" was itself inherently unequal. The NAACP said the two notions were incompatible. As one witness before the U.S. Commune Courtroom of Kansas said, "The unabridged colored race is craving low-cal, and the just way to reach the lite is to get-go [blackness and white] children together in their infancy and they come upwards together."16

To brand its instance, the NAACP marshaled historical and social scientific bear witness. The Court found the historical bear witness inconclusive and drew their ruling more heavily from the NAACP's argument that segregation psychologically damaged Blackness children. To make this argument, association lawyers relied on social scientific testify, such as the famous doll experiments of Kenneth and Mamie Clark. The Clarks demonstrated that while immature white girls would naturally choose to play with white dolls, young Blackness girls would, also. The Clarks argued that Black children's aesthetic and moral preference for white dolls demonstrated the pernicious effects and self-loathing produced by segregation.

Identifying and denouncing injustice, though, is different from rectifying information technology. Though Brown repudiated Plessy, the Courtroom'southward orders did not extend to segregation in places other than public schools and, even and so, to preserve a unanimous decision for such an historically important case, the justices set aside the divisive nevertheless essential question of enforcement. Their infamously cryptic guild in 1955 (what came to be known as Brown II) that school districts desegregate "with all deliberate speed" was so vague and ineffectual that it left the actual business of desegregation in the hands of those who opposed it.

In 1959, photographer John Bledsoe captured this image of the oversupply on the steps of the Arkansas state capitol building protesting the federally mandated integration of Little Stone's Central Loftier School. This image shows how worries almost desegregation were bound upwards with other concerns, such as the reach of communism and government ability. Library of Congress.

In almost of the South, as well as the rest of the country, school integration did not occur on a wide scale until well after Brown. Only in the 1964 Civil Rights Act did the federal government finally implement some enforcement of the Dark-brown decision past threatening to withhold funding from recalcitrant school districts, but fifty-fifty then southern districts found loopholes. Court decisions such as Green five. New Kent County (1968) and Alexander five. Holmes (1969) finally closed some of those loopholes, such as "freedom of choice" plans, to compel some measure out of actual integration.

When Brownish finally was enforced in the South, the quantitative impact was staggering. In 1968, 14 years subsequently Brown, some eighty percentage of school-age Black southerners remained in schools that were 90 to 100 percent nonwhite. By 1972, though, merely 25 percent were in such schools, and 55 per centum remained in schools with a elementary nonwhite minority. By many measures, the public schools of the Southward became, ironically, the most integrated in the nation.17

Every bit a landmark moment in American history, Brown'due south significance perhaps lies less in immediate tangible changes—which were slow, fractional, and inseparable from a much longer chain of events—than in the idealism it expressed and the momentum it created. The nation's highest court had attacked one of the fundamental supports of Jim Crow segregation and offered constitutional cover for the creation of one of the greatest social movements in American history.

IV. Ceremonious Rights in an Affluent Lodge

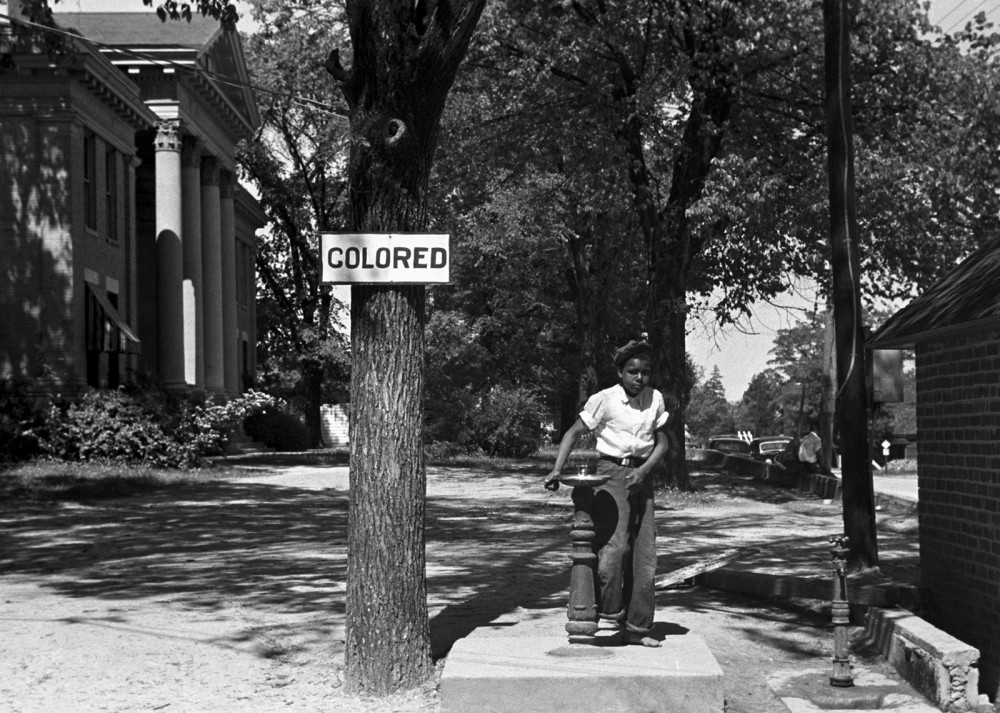

This segregated drinking fountain was located on the grounds of the Halifax County courthouse in North Carolina. Photograph, April 1938. Wikimedia.

Pedagogy was only one aspect of the nation'south Jim Crow mechanism. African Americans had been fighting confronting a variety of racist policies, cultures, and beliefs in all aspects of American life. And while the struggle for Blackness inclusion had few victories earlier World State of war II, the state of war and the Double V campaign for victory against fascism abroad and racism at home, as well as the postwar economic smash led, to ascension expectations for many African Americans. When persistent racism and racial segregation undercut the promise of economic and social mobility, African Americans began mobilizing on an unprecedented scale against the various discriminatory social and legal structures.

While many of the civil rights motion'due south most memorable and important moments, such as the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, and especially the March on Washington, occurred in the 1960s, the 1950s were a significant decade in the sometimes tragic, sometimes triumphant march of civil rights in the Usa. In 1953, years before Rosa Parks's iconic confrontation on a Montgomery city bus, an African American woman named Sarah Keys publicly challenged segregated public transportation. Keys, and so serving in the Women's Army Corps, traveled from her regular army base in New Jersey back to North Carolina to visit her family. When the bus stopped in North Carolina, the driver asked her to give upward her seat for a white client. Her refusal to do so landed her in jail in 1953 and led to a landmark 1955 conclusion, Sarah Keys 5. Carolina Coach Company, in which the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled that "split up but equal" violated the Interstate Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Poorly enforced, it nonetheless gave legal coverage for the Liberty Riders years later and motivated further assaults confronting Jim Crow.

But if some events encouraged civil rights workers with the promise of progress, others were so savage they convinced activists that they could practise nothing merely resist. In the summer of 1955, two white men in Mississippi kidnapped and brutally murdered fourteen-year-old Emmett Till. Till, visiting from Chicago and possibly unfamiliar with the "etiquette" of Jim Crow, allegedly whistled at a white woman named Carolyn Bryant. Her husband, Roy Bryant, and another homo, J. W. Milam, abducted Till from his relatives' abode, beat him, mutilated him, shot him, and threw his body in the Tallahatchie River. Emmett'southward mother held an open-catafalque funeral then that Till'southward disfigured body could brand national news. The men were brought to trial. The prove was damning, but an all-white jury institute the two non guilty. Mere months after the decision, the ii boasted of their crime, in all of its brutal detail, in Look magazine. "They ain't gonna become to school with my kids," Milam said. They wanted "to make an example of [Till]—simply and then everybody tin know how me and my folks stand."18 The Till case became an indelible retention for the immature Black men and women soon to propel the ceremonious rights motion forrard.

On Dec 1, 1955, iv months after Till'south expiry and six days after the Keys v. Carolina Omnibus Company decision, Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat on a Montgomery urban center double-decker and was arrested. Montgomery's public transportation system had longstanding rules requiring African American passengers to sit in the back of the double-decker and to surrender their seats to white passengers if the buses filled. Parks was non the first to protest the policy by staying seated, but she was the first around whom Montgomery activists rallied.

Montgomery'southward Black population, under the leadership of local ministers and civil rights workers, formed the Montgomery Improvement Clan (MIA) and coordinated an organized boycott of the city's buses. The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted from Dec 1955 until December 20, 1956, when the Supreme Court ordered their integration. The cold-shoulder not only crushed segregation in Montgomery's public transportation, information technology energized the entire civil rights movement and established the leadership of the MIA'due south president, a recently arrived, twenty-six-year-old Baptist government minister named Martin Luther Rex Jr.

Motivated by the success of the Montgomery boycott, Rex and other African American leaders looked to go on the fight. In 1957, King helped create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to coordinate civil rights groups across the Southward and buoy their efforts organizing and sustaining boycotts, protests, and other assaults confronting southern Jim Crow laws.

As pressure built, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the outset such measure passed since Reconstruction. The act was compromised away near to goose egg, although it did achieve some gains, such as creating the Department of Justice's Ceremonious Rights Commission, which was charged with investigating claims of racial discrimination. And still, despite its weakness, the human action signaled that pressure was finally mounting on Americans to confront the legacy of discrimination.

Despite successes at both the local and national level, the civil rights move faced bitter opposition. Those opposed to the motion oftentimes used fierce tactics to scare and intimidate African Americans and subvert legal rulings and court orders. For example, a yr into the Montgomery motorbus boycott, angry white southerners bombed 4 African American churches likewise as the homes of King and fellow civil rights leader East. D. Nixon. Though King, Nixon, and the MIA persevered in the face of such violence, information technology was merely a taste of things to come. Such unremitting hostility and violence left the outcome of the burgeoning civil rights movement in dubiety. Despite its successes, civil rights activists looked back on the 1950s as a decade of mixed results and incomplete accomplishments. While the bus cold-shoulder, Supreme Courtroom rulings, and other civil rights activities signaled progress, church bombings, expiry threats, and stubborn legislators demonstrated the distance that nonetheless needed to be traveled.

V. Gender and Culture in the Flush Society

Equally shown in this 1958 advertisement for a "Westinghouse with Cold Injector," a midcentury marketing frenzy targeted female consumers by touting technological innovations designed to make housework easier. Westinghouse.

America's consumer economic system reshaped how Americans experienced culture and shaped their identities. The Affluent Social club gave Americans new experiences, new outlets, and new means to sympathize and interact with one another.

"The American household is on the threshold of a revolution," the New York Times declared in August 1948. "The reason is tv set."19 Idiot box was presented to the American public at the New York World'south Fair in 1939, but commercialization of the new medium in the U.s. lagged during the war years. In 1947, though, regular total-scale broadcasting became available to the public. Goggle box was instantly popular, so much so that by early 1948 Newsweek reported that it was "catching on like a case of high-toned scarlet fever."20 Indeed, betwixt 1948 and 1955 close to 2 thirds of the nation's households purchased a boob tube set. By the end of the 1950s, xc percent of American families had one and the average viewer was tuning in for most five hours a day.21

The technological power to transmit images via radio waves gave birth to goggle box. Television borrowed radio'south organizational construction, too. The large radio broadcasting companies—NBC, CBS, and the American Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)—used their technical expertise and capital reserves to conquer the airwaves. They acquired licenses to local stations and eliminated their few contained competitors. The refusal of the Federal Advice Commission (FCC) to issue whatever new licenses between 1948 and 1955 was a de facto endorsement of the big three'due south stranglehold on the market.

In improver to replicating radio's organizational structure, television also looked to radio for content. Many of the early programs were adaptations of pop radio variety and one-act shows, including The Ed Sullivan Prove and Milton Berle'due south Texaco Star Theater. These were accompanied past live plays, dramas, sports, and situation comedies. Because of the cost and difficulty of recording, about programs were broadcast live, forcing stations beyond the country to air shows at the aforementioned fourth dimension. And since audiences had a limited number of channels to cull from, viewing experiences were broadly shared. More than than ii thirds of idiot box-owning households, for instance, watched pop shows such every bit I Love Lucy.

The limited number of channels and programs meant that networks selected programs that appealed to the widest possible audience to draw viewers and advertisers, tv set's greatest financers. By the mid-1950s, an hour of primetime programming cost nigh $150,000 (nigh $one.5 million in today's dollars) to produce. This proved besides expensive for most commercial sponsors, who began turning to a joint financing model of xxx-second spot ads. The need to appeal to as many people as possible promoted the production of noncontroversial shows aimed at the entire family. Programs such equally Father Knows Best and Exit information technology to Beaver featured lite topics, sense of humor, and a guaranteed happy ending the whole family could bask.22

Ad was everywhere in the 1950s, including on Telly shows such every bit the quiz prove Twenty I, sponsored by Geritol, a dietary supplement. Library of Congress.

Television's broad appeal, however, was about more than money and amusement. Shows of the 1950s, such as Father Knows Best and I Love Lucy, idealized the nuclear family, "traditional" gender roles, and white, middle-grade domesticity. Go out It to Beaver, which became the prototypical example of the 1950s television family unit, depicted its breadwinner father and homemaker mother guiding their children through life lessons. Such shows, and Cold War America more broadly, reinforced a popular consensus that such lifestyles were non only beneficial simply the most constructive style to safeguard American prosperity against communist threats and social "deviancy."

Postwar prosperity facilitated, and in turn was supported past, the ongoing postwar baby boom. From 1946 to 1964, American fertility experienced an unprecedented spike. A century of failing nativity rates abruptly reversed. Although popular retention credits the cause of the baby smash to the return of virile soldiers from boxing, the real story is more nuanced. Afterward years of economic depression, families were now wealthy plenty to support larger families and had homes large plenty to suit them, while women married younger and American culture celebrated the ideal of a big, insular family.

Underlying this "reproductive consensus" was the new cult of professionalism that pervaded postwar American civilization, including the professionalization of homemaking. Mothers and fathers alike flocked to the experts for their opinions on matrimony, sexuality, and, nigh especially, child-rearing. Psychiatrists held an almost mythic status as people took their opinions and prescriptions, equally well every bit their vocabulary, into their everyday life. Books similar Dr. Spock'due south Baby and Child Intendance (1946) were diligently studied by women who took their career as housewife equally just that: a career, consummate with all the demands and professional trappings of task development and training. And since most women had multiple children roughly the same historic period every bit their neighbors' children, a cultural obsession with kids flourished throughout the era. Women diameter the brunt of this force per unit area, chided if they did not give plenty of their fourth dimension to the children—particularly if it was because of a career—yet cautioned that spending likewise much time would lead to "Momism," producing "sissy" boys who would be incapable of contributing to gild and extremely susceptible to the communist threat.

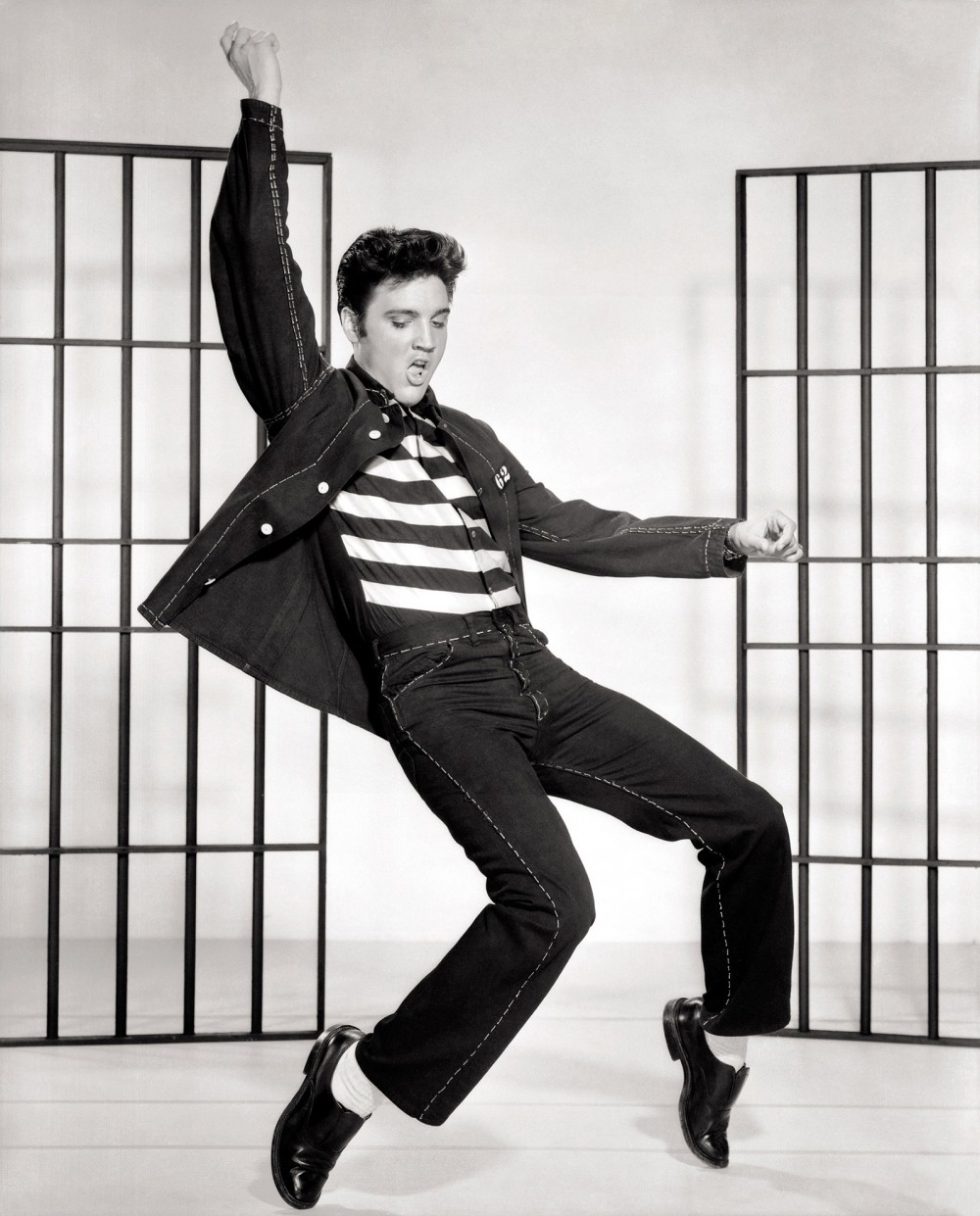

A new youth civilization exploded in American popular civilization. On the one hand, the anxieties of the atomic age hit America's youth specially hard. Keenly aware of the discontent bubbling beneath the surface of the Affluent Order, many youth embraced rebellion. The 1955 pic Rebel Without a Cause demonstrated the restlessness and emotional dubiousness of the postwar generation raised in increasing abundance yet increasingly unsatisfied with their comfy lives. At the same time, perhaps yearning for something beyond the "massification" of American culture however having few other options to plough to across popular civilisation, American youth embraced rock 'due north' roll. They listened to Little Richard, Buddy Holly, and especially Elvis Presley (whose sexually suggestive hip movements were judged subversive).

The popularity of rock 'northward' gyre had not yet blossomed into the countercultural musical revolution of the coming decade, simply it provided a magnet for teenage restlessness and rebellion. "Television and Elvis," the musician Bruce Springsteen recollected, "gave us full admission to a new language, a new form of advice, a new way of being, a new mode of looking, a new fashion of thinking; about sex, nigh race, about identity, about life; a new mode of beingness an American, a human; and a new fashion of hearing music." American youth had seen and then little of Elvis'south energy and sensuality elsewhere in their civilisation. "Once Elvis came across the airwaves," Springsteen said, "one time he was heard and seen in action, y'all could non put the genie back in the canteen. After that moment, there was yesterday, and there was today, and there was a red hot, rockabilly forging of a new tomorrow, before your very optics."23

While many Black musicians such as Chuck Berry helped pioneer rock 'northward' roll, white artists such equally Elvis Presley brought it into the mainstream American culture. Elvis'due south skillful looks, sensual dancing, and sonorous voice stole the hearts of millions of American teenage girls, who were at that moment condign a cardinal segment of the consumer population. Wikimedia.

Other Americans took larger steps to reject the expected conformity of the Flush Society. The writers, poets, and musicians of the Beat Generation, disillusioned with capitalism, consumerism, and traditional gender roles, sought a deeper meaning in life. Beats traveled across the land, studied Eastern religions, and experimented with drugs, sex, and art.

Behind the scenes, Americans were challenging sexual mores. The gay rights movement, for instance, stretched back into the Affluent Society. While the country proclaimed homosexuality a mental disorder, gay men established the Mattachine Gild in Los Angeles and gay women formed the Daughters of Bilitis in San Francisco as support groups. They held meetings, distributed literature, provided legal and counseling services, and formed chapters across the state. Much of their work, however, remained secretive because homosexuals risked arrest and abuse if discovered.24

Society's "consensus," on everything from the consumer economy to gender roles, did non go unchallenged. Much discontent was channeled through the machine itself: advertisers sold rebellion no less than they sold baking soda. And yet others were rejecting the old ways, choosing new lifestyles, challenging former hierarchies, and embarking on new paths.

Six. Politics and Ideology in the Affluent Social club

Postwar economic prosperity and the creation of new suburban spaces inevitably shaped American politics. In stark contrast to the Dandy Depression, the new prosperity renewed belief in the superiority of commercialism, cultural conservatism, and religion.

In the 1930s, the economic ravages of the international economic catastrophe knocked the legs out from under the intellectual justifications for keeping government out of the economy. And yet pockets of true believers kept alive the gospel of the complimentary marketplace. The unmarried most important was the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). In the midst of the depression, NAM reinvented itself and went on the offensive, initiating advertising campaigns supporting "gratuitous enterprise" and "The American Way of Life."25 More importantly, NAM became a node for business leaders, such as J. Howard Pew of Sun Oil and Jasper Crane of DuPont Chemical Co., to network with like-minded individuals and take the message of free enterprise to the American people. The network of business organization leaders that NAM brought together in the midst of the Keen Low formed the financial, organizational, and ideological underpinnings of the free market advocacy groups that emerged and found ready adherents in America'due south new suburban spaces in the postwar decades.

1 of the most of import advocacy groups that sprang up after the state of war was Leonard Read'south Foundation for Economic Teaching (FEE). Read founded FEE in 1946 on the premise that "The American Way of Life" was essentially individualistic and that the best way to protect and promote that individualism was through libertarian economics. Libertarianism took every bit its cadre principle the promotion of individual freedom, property rights, and an economy with a minimum of authorities regulation. FEE, whose advisory lath and supporters came mostly from the NAM network of Pew and Crane, became a key ideological factory, supplying businesses, service clubs, churches, schools, and universities with a steady stream of libertarian literature, much of it authored past Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises.26

Shortly later FEE's formation, Austrian economist and libertarian intellectual Friedrich Hayek founded the Mont Pelerin Guild (MPS) in 1947. The MPS brought together libertarian intellectuals from both sides of the Atlantic to claiming Keynesian economic science—the dominant notion that regime financial and budgetary policy were necessary economical tools—in academia. University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman became its president. Friedman (and his Chicago School of Economics) and the MPS became some of the well-nigh influential costless market advocates in the world and helped legitimize for many the libertarian ideology so successfully evangelized past FEE, its descendant organizations, and libertarian popularizers such as the novelist Ayn Rand.27

Libertarian politics and evangelical religion were shaping the origins of a new bourgeois, suburban constituency. Suburban communities' altitude from government and other top-down customs-building mechanisms—despite relying on authorities subsidies and government programs—left a social void that evangelical churches eagerly filled. More often than not the theology and ideology of these churches reinforced socially conservative views while simultaneously reinforcing congregants' conventionalities in economic individualism. Novelist Ayn Rand, meanwhile, whose novels The Fountainhead (1943) and Atlas Shrugged (1957) were two of the decades' best sellers, helped motility the ideas of individualism, "rational cocky-involvement," and "the virtue of selfishness" outside the halls of business and academia and into suburbia. The ethos of individualism became the building blocks for a new political movement. And yet, while the growing suburbs and their brewing conservative ideology eventually proved immensely of import in American political life, their impact was not immediately felt. They did not yet have a champion.

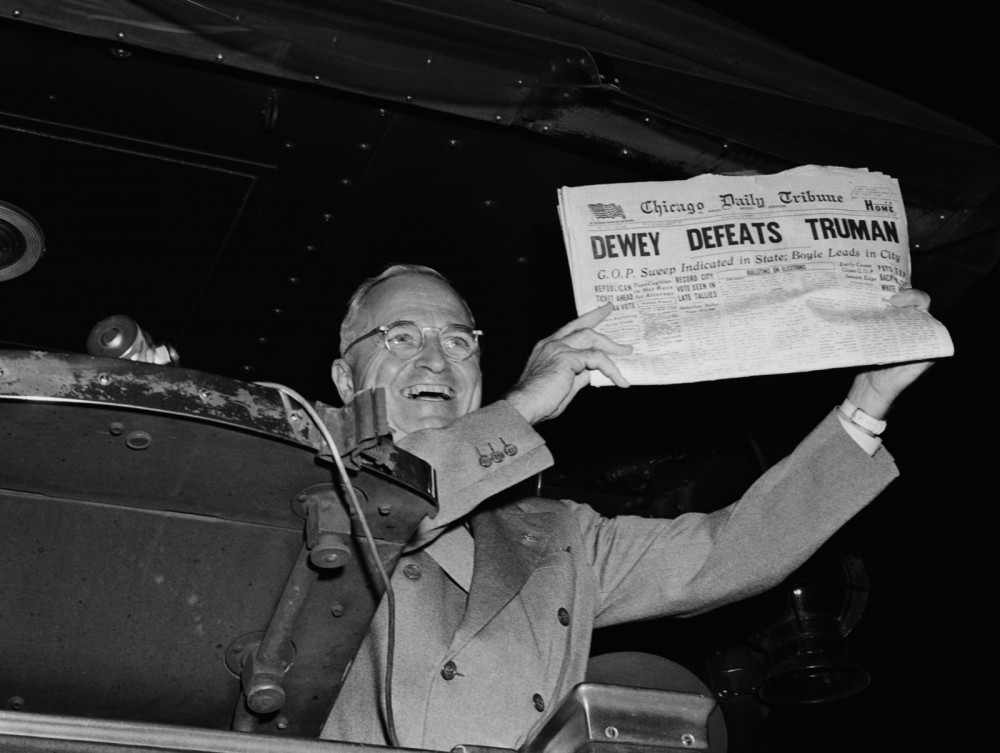

In the mail service–Globe War II years the Republican Party faced a fork in the road. Its complete lack of electoral success since the Low led to a battle within the party nigh how to revive its electoral prospects. The more conservative faction, represented by Ohio senator Robert Taft (son of former president William Howard Taft) and backed by many party activists and financiers such as J. Howard Pew, sought to take the party further to the right, particularly in economic matters, by rolling dorsum New Deal programs and policies. On the other hand, the more moderate fly of the party, led by men such equally New York governor Thomas Dewey and Nelson Rockefeller, sought to embrace and reform New Bargain programs and policies. There were further disagreements among party members about how involved the United States should be in the world. Bug such as foreign aid, collective security, and how best to fight communism divided the party.

Only similar the net, don't always trust what you read in newspapers. This evidently incorrect banner from the forepart folio of the Chicago Daily Tribune on Nov 3, 1948 made its own headlines as the newspaper'south nigh embarrassing gaff. Photograph, 1948. http://media-2.web.britannica.com/eb-media/14/65214-050-D86AAA4E.jpg. Undated portrait of President Harry Due south. Truman. National Archives.

Initially, the moderates, or "liberals," won command of the party with the nomination of Thomas Dewey in 1948. Dewey'due south shocking loss to Truman, nevertheless, emboldened conservatives, who rallied effectually Taft as the 1952 presidential primaries approached. With the conservative banner riding high in the political party, Full general Dwight Eisenhower ("Ike"), most recently Northward Atlantic Treaty System (NATO) supreme commander, felt obliged to join the race in order to beat back the conservatives and "prevent one of our groovy two Parties from adopting a course which could atomic number 82 to national suicide." In addition to his fear that Taft and the conservatives would undermine commonage security arrangements such as NATO, he also berated the "neanderthals" in his party for their anti–New Deal stance. Eisenhower felt that the best way to stop communism was to undercut its appeal by alleviating the conditions under which information technology was most bonny. That meant supporting New Deal programs. There was also a political calculus to Eisenhower's position. He observed, "Should any party endeavour to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history."28

The principal contest between Taft and Eisenhower was shut and controversial. Taft supporters claimed that Eisenhower stole the nomination from Taft at the convention. Eisenhower, attempting to placate the conservatives in his party, picked California congressman and virulent anticommunist Richard Nixon as his running mate. With the Republican nomination sewn up, the immensely popular Eisenhower swept to victory in the 1952 general election, hands besting Truman's mitt-picked successor, Adlai Stevenson. Eisenhower'southward popularity additional Republicans across the country, leading them to majorities in both houses of Congress.

The Republican sweep in the 1952 election, attributable in part to Eisenhower'due south popularity, translated into few tangible legislative accomplishments. Within ii years of his election, the moderate Eisenhower saw his legislative proposals routinely defeated by an unlikely brotherhood of bourgeois Republicans, who thought Eisenhower was going too far, and liberal Democrats, who idea he was not going far enough. For case, in 1954 Eisenhower proposed a national healthcare plan that would have provided federal support for increasing healthcare coverage across the nation without getting the authorities straight involved in regulating the healthcare industry. The proposal was defeated in the business firm by a 238–134 vote with a swing bloc of seventy-five conservative Republicans joining liberal Democrats voting against the plan.29 Eisenhower's proposals in education and agriculture frequently suffered similar defeats. By the end of his presidency, Ike's domestic legislative achievements were largely limited to expanding social security; making Wellness, Didactics and Welfare (HEW) a chiffonier position; passing the National Defense force Education Human action; and bolstering federal back up to education, particularly in math and science.

Every bit with any president, still, Eisenhower's bear upon was bigger than just legislation. Ike's "middle of the road" philosophy guided his foreign policy every bit much as his domestic agenda. He sought to proceed the United States from direct interventions abroad past bolstering anticommunist and procapitalist allies. Ike funneled money to the French in Vietnam fighting the Ho Chi Minh–led communists, walked a tight line betwixt helping Chiang Kai-Shek'south Taiwan without overtly provoking Mao Zedong's Communist china, and materially backed groups that destabilized "unfriendly" governments in Islamic republic of iran and Guatemala. The centerpiece of Ike'due south Soviet policy, meanwhile, was the threat of "massive retaliation," or the threat of nuclear force in the face up of communist expansion, thereby checking Soviet expansion without direct American involvement. While Ike's "mainstream" "eye style" won broad popular back up, his ain party was slowly moving abroad from his positions. Past 1964 the party had moved far plenty to the correct to nominate Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, the most bourgeois candidate in a generation. The political moderation of the Affluent Society proved fiddling more than than a way station on the route to liberal reforms and a more distant bourgeois ascendancy.

Vii. Conclusion

The postwar American "consensus" held great promise. Despite the looming threat of nuclear war, millions experienced an unprecedented prosperity and an increasingly proud American identity. Prosperity seemed to promise ever higher standards of living. But things fell apart, and the heart could not hold: wracked by contradiction, dissent, discrimination, and inequality, the Affluent Society stood on the precipice of revolution.

Eight. Primary Sources

- Migrant Farmers and Immigrant Labor (1952)

During the labor shortages of World War 2, the United States' launched the Bracero ("laborer") plan to bring Mexican laborers into the United states of america. The program continued into the 1960s and brought more than than a meg workers into the U.s.a. on short-term contracts. Undocumented immigration continued, withal. Congress held hearings and, in the choice beneath, a migrant worker named Juanita Garcia testifies to Congress near the state of affairs in California'due south Purple Valley. Beginning in 1954, Dwight Eisenhower's administration oversaw, with the cooperation of the Mexican government, "Functioning Wetback," which empowered to the Border Patrol to scissure downwards upon illegal immigration.

2. Hernandez five. Texas (1954)

Pete Hernandez, a migrant worker, was tried for the murder of his employer, Joe Espinosa, in Edna, Texas, in 1950. Hernandez was convicted by an all-white jury. His lawyers appealed. They argued that Hernandez was entitled to a jury "of his peers" and that systematic exclusion of Mexican Americans violated ramble police. In a unanimous decision, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Mexican Americans—and all "classes"—were entitled to the "equal protection" articulated in the Fourteenth Subpoena.

3. Chocolate-brown v. Lath of Education of Topeka (1954)

In 1896, the Us Supreme Court declared inPlessy five. Fergusonthat the doctrine of "carve up but equal" was constitutional. In 1954, the United States Supreme Court overturned that determination and

4. Richard Nixon on the American Standard of Living (1959)

As Common cold State of war tensions eased, exhibitions allowed for Americans and Soviets to survey the other'due south culture and way of life. In 1959, the Russians held an exhibition in New York, and the Americans in Moscow. A videotaped discussion between Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev, the and then-chosen "Kitchen Fence," won Richard Nixon acclaim at home for his clear defence force of the American standard of living. In the following extract from July 24, 1959, Nixon opened the American Exhibition in Moscow.

v. John F. Kennedy on the Separation of Church and Country (1960)

American Anti-Catholicism had softened in the aftermath of Earth War Two, simply no Catholic had ever been elected president and Protestant Americans had long been suspicious of Cosmic politicians when John F. Kennedy ran for the presidency in 1960. (Al Smith, the kickoff Catholic presidential candidate, was roundly defeated in 1928 owing in large office to popular anti-Catholic prejudice). On September 12, 1960, Kennedy addressed the Greater Houston Ministerial Association and he non only allayed pop fears of his Catholic faith, he delivered a seminal statement on the separation of church and land.

six. Congressman Arthur L. Miller Gives "the Putrid Facts" Nearly Homosexuality (1950)

In 1950, Representative Arthur Fifty. Miller, a Nebraska Republican, offered an amendment to a bill requiring background checks for employees of the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA). Miller proposed to bar homosexuals from working with the ECA. Although his amendment was rejected, his views of homosexuality revealed much nearly postwar American views.

7. Rosa Parks on Life in Montgomery, Alabama (1956-1958)

In this unfinished correspondence and undated personal notes, Rosa Parks recounted living under segregation in Montgomery, Alabama, explained why she refused to give up her seat on a metropolis bus, and lamented the psychological toll exacted by Jim Crow.

eight. Little Rock Rally (1959)

In 1959, photographer John Bledsoe captured this image of the crowd on the steps of the Arkansas state capitol edifice, protesting the federally mandated integration of Fiddling Stone'southward Central Loftier Schoolhouse. This image shows how worries about desegregation were bound up with other concerns, such every bit the accomplish of communism and regime power.

9. "In the Suburbs" (1957)

Redbook fabricated this motion picture to convince advertisers that the magazine would assist them attract the white suburban consumers they desired. The "happy go spending, purchase information technology now, young adults of today" are depicted past the film every bit flocking to the suburbs to escape global and urban turmoil. Redbook Magazine, "In The Suburbs" (1957). Via The Net Annal.

IX. Reference Material

This chapter was edited by James McKay, with content contributions past Edwin C. Breeden, Aaron Cowan, Elsa Devienne, Maggie Flamingo, Destin Jenkins, Kyle Livie, Jennifer Mandel, James McKay, Laura Redford, Ronny Regev, and Tanya Roth.

Recommended citation: Edwin C. Breeden et al., "The Cold War," James McKay, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Printing, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Boyle, Kevin. The UAW and the Heyday of American Liberalism, 1945–1968. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.

- Branch, Taylor. Departing the Waters: America in the Rex Years, 1954–1963. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

- Dark-brown, Kate. Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2013.

- Brownish-Nagin, Tomiko. Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Move. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. A Consumer's Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. New York: Knopf, 2003.

- Coontz, Stephanie. The Fashion We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. New York: Basic Books, 1993.

- Dudziak, Mary. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Commonwealth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 2002.

- Fried, Richard M. Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Grisinger, Joanna. The Unwieldy American State: Administrative Politics Since the New Deal. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Hernández, Kelly Lytle. Migra! A History of the U.S. Border Patrol. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- Horowitz, Daniel. Betty Friedan and the Making of the Feminine Mystique: The American Left, the Cold War, and Modern Feminism. Amherst: Academy of Massachusetts Press, 1998.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Printing, 1985.

- Jumonville, Neil. Critical Crossings: The New York Intellectuals in Postwar America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- Levenstein, Lisa. A Movement Without Marches: African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia. Chapel Hill: University of N Carolina Printing, 2009.

- May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

- McGirr, Lisa. Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Correct. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 2001.

- Ngai, Mae. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 2003.

- Patterson, James T. Grand Expectations: The United states, 1945–1974. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1996.

- Roberts, Gene, and Hank Klibanoff. The Race Beat: The Printing, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. New York: Knopf, 2006.

- Self, Robert. American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 2005.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Von Eschen, Penny. Satchmo Blows Upwardly the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold State of war. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Wagnleitner, Reinhold. Coca-Colonization and the Cold War: The Cultural Mission of the Usa in Austria Afterward the 2d World War. Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina Press, 1994.

- Wall, Wendy. Inventing the "American Way": The Politics of Consensus from the New Deal to the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Whitfield, Stephen. The Culture of the Cold State of war. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

Notes

- John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1958), 129. [↩]

- See, for example, Claudia Goldin and Robert A. Margo, "The Swell Compression: The Wage Structure in the United States at Mid-Century," Quarterly Journal of Economic science 107 (February 1992), 1–34. [↩]

- Price Fishback, Jonathan Rose, and Kenneth Snowden, Well Worth Saving: How the New Bargain Safeguarded Home Ownership (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). [↩]

- Leo Schnore, "The Growth of Metropolitan Suburbs," American Sociological Review 22 (April 1957), 169. [↩]

- Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers' Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (New York: Random Firm, 2002), 202. [↩]

- Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Leap: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York, Basic Books, 1999), 152. [↩]

- Leo Fishman, The American Economy (Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand, 1962), 560. [↩]

- John P. Diggins, The Proud Decades: America in State of war and in Peace, 1941–1960 (New York: Norton, 1989), 219. [↩]

- David Kushner, Levittown: Two Families, One Tycoon, and the Fight for Civil Rights in America's Legendary Suburb (New York: Bloomsbury Printing, 2009), 17. [↩]

- Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crunch: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). [↩]

- Becky One thousand. Nicolaides, My Blue Heaven: Life and Politics in the Working–Class Suburbs of Los Angeles, 1920-1965 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 193. [↩]

- Adam W. Rome, The Bulldozer in the Countryside: Suburban Sprawl and the Ascent of American Environmentalism (Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press, 2001), 7. [↩]

- See also J. R. McNeill and Peter Engelke,The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Academy Press, 2016); Andrew Needham,Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modernistic Southwest(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014); and Ted Steinberg,Downward to Earth: Nature's Office in American History(New York: Oxford University Press, 2002). [↩]

- Oliver Dark-brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al., 347 U.S. 483 (1954). [↩]

- James T. Patterson and William W. Freehling, Brown five. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (New York: Oxford University Printing, 2001), 25; Pete Daniel, Standing at the Crossroads: Southern Life in the Twentieth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Printing, 1996), 161–164. [↩]

- Patterson and Freehling, Dark-brown 5. Lath, xxv. [↩]

- Charles T. Clotfelter, After Chocolate-brown: The Rising and Retreat of School Desegregation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 6. [↩]

- William Bradford Huie, "The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi," Look (Jan 24, 1956), 46–fifty. [↩]

- Lewis Fifty. Gould, Watching Television Come of Historic period: The New York Times Reviews by Jack Gould (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), 186. [↩]

- Gary Edgerton, Columbia History of American Goggle box (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 90. [↩]

- Ibid., 178. [↩]

- Christopher H. Sterling and John Michael Kittross, Stay Tuned: A History of American Dissemination (New York: Routledge, 2001), 364. [↩]

- Bruce Springsteen, "SXSW Keynote Address," Rolling Stone (March 28, 2012), http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/exclusive-the-consummate-text-of-bruce-springsteens-sxsw-keynote-address-20120328. [↩]

- John D'Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, 2d ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 102–103. [↩]

- See Richard Tedlow, "The National Association of Manufacturers and Public Relations During the New Deal," Business History Review fifty (Spring 1976), 25–45; and Wendy Wall, Inventing the "American Manner": The Politics of Consensus from the New Deal to the Civil Rights Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008). [↩]

- Gregory Eow, "Fighting a New Deal: Intellectual Origins of the Reagan Revolution, 1932–1952," PhD diss., Rice Academy, 2007; Brian Doherty, Radicals for Commercialism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Motility (New York: Public Diplomacy, 2007); and Kim Phillips Fein, Invisible Hands: The Businessmen's Crusade Confronting the New Deal (New York: Norton, 2009), 43–55. [↩]

- Angus Burgin, The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Complimentary Markets Since the Depression (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012); Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Correct (New York: Oxford University Printing, 2009). [↩]

- Allan J. Lichtman, White Protestant Nation: The Ascension of the American Bourgeois Movement (New York: Atlantic Monthly Printing, 2008), 180, 201, 185. [↩]

- Steven Wagner, Eisenhower Republicanism Pursuing the Middle Way (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Printing, 2006), fifteen. [↩]

Source: https://www.americanyawp.com/text/26-the-affluent-society/

0 Response to "Apush Chapter 28 Review Questions Identification Iron Curtain"

Postar um comentário